By Tonia Wright

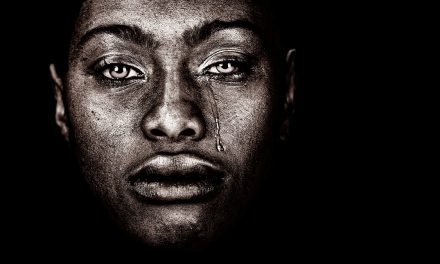

If you are fatigued from the hate-filled vitriol televised or posted daily, you are in good company… so is former First Lady Michelle Obama. In the second episode of her new podcast, The Michelle Obama Podcast, she spoke with friend Michele Norris and former longtime host of NPR’s All Things Considered. “I know that I am dealing with some form of low-grade depression,” Mrs. Obama said. “Not just because of quarantine, but because of the racial strife, and just seeing this administration, watching the daily hypocrisy of it all, day in and day out, is dispiriting.”

Racism, discrimination, and marginalization are the prerequisites for depression, anxiety, PTSD, and other disorders that fuel racial health care disparities. Arline Geronimus, Sc.D., Professor of Public Health at the University of Michigan, calls this “weathering, the cumulative effect of stress resulting from racial discrimination, long-term exposure to environmental toxins, redlining that limits essential services, disproportionate victimization by crime…” and the proverbial list for people of color continues. Geronimus likens weathering to the body’s way of eroding due to constant stress and marginalization.

In ScienceDirect’s published abstract on Racial Differences in Weathering and its Associations with Psychosocial Stress: The CARDIA Study, biological age (BA) is defined as a “construct that captures accelerated biological age attributed to wear and tear from various exposures.” The weathering hypothesis, which Geronimus coined, is now recognized by scholars and researchers as the measured distance from BA and chronological age, and how that dichotomy correlates with race and psychosocial factors.

The Link Between Experiences of Racism and Stress and Anxiety for Black Americans: A Mindfulness and Acceptance-Based Coping Approach, published on Anxiety.org, notes racism experienced at all levels has significant negative effects on both physical and mental health outcomes. Mrs. Obama also spoke to this in her podcast. “Waking up to yet another story of a black man or a black person somehow being dehumanized, or hurt, or killed, or falsely accused of something, it is exhausting.”

Some research has suggested that chronic experiences of racism and microaggressions result in racial battle fatigue that causes anxiety and worry, hypervigilance, headaches, increased heart rate and blood pressure, as well as other physical and psychological symptoms.

According to the authors, experiences of racism that lead to stress and anxiety can manifest for some black people in three harmful ways: perceptions of lack of control over one’s environment; internalized racism and negative self-evaluation; and avoiding distressing emotions. The article states that one in four black Americans will experience an anxiety disorder at some point in life and is more likely to suffer from social anxiety disorder. According to the article, symptoms associated with anxiety persist longer for black Americans compared with the general population.

The CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk in Young Adults) study backs this up. It used a middle-aged, bi-racial cohort in four U.S. cities from 1985-2016 to examine weathering for adults aged 48-60 years. Using selected biomarkers (measurable factors that indicate disease, infection, environmental exposure, etc.), the study assessed overall race-specific associations between weathering and psychosocial measures.

For the 2,694 participants, blacks had a BA 11.8 years older than their chronological age, compared with whites, who had an average BA 10.0 years younger than their chronological age. Researchers conclude that black people show accelerated biological age (weathering) compared with whites; psychosocial factors are associated with weathering; and psychosocial factors are more strongly associated with weathering among blacks.

Not long ago, weathering was dismissed by the media and scholars as nothing more than black people making poor life choices and having inferior DNA. Some in the medical community concluded that health disparities among black people were intrinsically genetic, or the black-white differences in health must be caused by some gene.

Some of these conclusions were bizarre and far-fetched, like the “hypertension gene” that followed slaves from Africa onto slave ships and through the Middle Passage, infusing surviving slaves with a propensity for salt retention, thus making them more susceptible to hypertension. Geronimus said that notion was easily debunked as American blacks and blacks from the Caribbean both went through the Middle Passage, yet American blacks have a far higher rate of hypertension.

In more recent years, research and genetic science dispelled the DNA myth and embraced Geronimus’ weathering theory. In an NPR story, Making the Case that Discrimination is Bad for Your Health, Geronimus explains weathering as chronic stressors that afflict people of color as [lifetime] stressors, often occurring in young adulthood through middle age as opposed to earlier in life.

Geronimus recalls an interview with Emerald Garner-Snipes about the death of her sister Erica Garner-Snipes, daughters of Eric Garner who died at the hands of police after being put in a chokehold. “She talked about the stresses that she felt led to Erica’s death at age 27 as being like if you’re playing the game Jenga. They pull out one piece at a time, at a time, and another piece and another piece, until you sort of collapse,” Geronimus told NPR, paraphrasing Emerald’s analogy. “I thought the Jenga metaphor was very apt because you start losing pieces of your health and well-being but you still try to go on as long as you can. Even if you’re disabled, even if it’s hard, that you have a certain tenacity and hope, and sense of collective responsibility whether that’s for your family or community. But there’s a point where enough pieces have been pulled out of you, that you can no longer withstand, and you collapse.”

Geronimus further correlates weathering with maternal and infant mortality rates. Young (teenage) black women had fewer problems giving birth. However, Geronimus notes these women had more complications the later they waited to have children. “The impacts on their bodies had been happening for a longer period of time,” she said. (It is important to note that the data Geronimus pointed to indicate an opposite reality for white women. They experienced higher risks during teen years and lower risks around mid-twenties.)

The U.S. has the highest maternal and infant mortality rates of other comparably developed countries. The survival rates for black mothers and their infants – regardless of education, socioeconomic status, etc. are three to four times the rate of non-Hispanic white women, while the death rate for black infants is twice that of infants born to non-Hispanic white mothers – one of the widest racial disparities in women’s health.

As for the weathering effect in black women of a certain childbearing age, sadly, Erica Garner-Snipes is one case in point. Three years ago, she gave birth to a son, and shortly afterward suffered her first heart attack. Garner-Snipes, a Black Lives Matter activist, became a stalwart for social justice after the death of her father in 2014. Suffering from an enlarged heart, potentially due to the stress of pregnancy and her father’s death, she suffered a second heart attack four months after the first one that put her in a coma. She died on December 30, 2017.

Tennis champion Serena Williams also nearly died from pregnancy-related complications. Megastar Beyoncé Knowles-Carter experienced pregnancy complications due to toxemia and preeclampsia when she gave birth to twins in 2017. According to a piece co-published by ProPublica and NPR, black women, regardless of socioeconomic status, are 22% more likely to die from heart disease than white women, 71% more likely to die from cervical cancer, and 243% more likely to die from pregnancy- or childbirth-related causes.

Another article, Exploring African Americans’ High Maternal and Infant Death Rate, suggests “stress induced by this discrimination plays a significant role in maternal and infant mortality.” Research further underscores the impacts of institutional racism and sexism that compromise women’s health over time, leading to poor outcomes for African American women and infants. This is coupled with a health care system mired by conscious and unconscious bias. “It is racism, not race itself, that threatens the lives of African American women and infants,” the article states.

There are other risk factors that researchers study using variables like poverty and low socioeconomic status, prenatal care, physical, and mental health. Overwhelmingly the conclusion is although black women are more likely than non-Hispanic white women to endure these disparities, this likelihood does not fully square the racial gap in outcomes; rather, these disparities stem from racial and gender discrimination over the lifespan of black women.

Social injustice and health inequity run in the same circle. Solutions to counteract the physio-psychological weathering of black people is more than complex. However, one reasonable response is active, coordinated, and sustained mobilization to destabilize institutional and structural racism at its core. The power of one’s vote is a mechanism to begin the process of dismantling political weaponry aimed at ensuring true democracy is never realized, for true, unadulterated democracy cannot coexist with racism. To this end, we must vote like our lives depend on it. As the late civil rights icon John Lewis wrote in the New York Times, the last opinion piece he would ever pen, “Democracy is not a state. It’s an act…”