In November, news broke that the number of migrant children separated from their families at the U.S.-Mexico border increased to 666, prompting an immediate outrage that just as quickly fizzled out of the national spotlight. There is a public demand, especially from the Latinx population, to keep the reality of what is happening at the border in the public’s mind and work to bring justice to the families affected. The atrocious conditions of the facilities, including insufficient access to food or hygienic care, raise severe health concerns while whistleblower reports of medical abuse of women detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) recently sparked investigations.

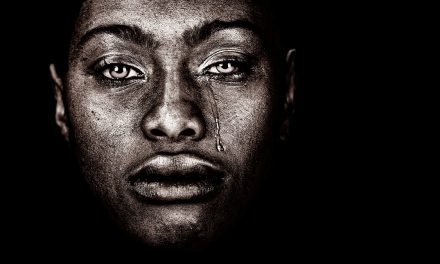

Aside from the obvious health issues, especially as the COVID-19 pandemic ravages prison populations in similar conditions at more than five times the national rate, the psychological impact of what detainees and their families are facing at the border will have devastating short-term and long-term effects. Two therapists specializing in trauma in the Kansas and Missouri area fear the impact these separations will cause in the future for both the children developing relationships and the parents reestablishing trust.

Jacey Bishop, a licensed specialist clinical social worker (LSCSW) specializing in trauma, abusive relationships, persistent mental illness and addiction, stresses that the very decision to immigrate and the journey itself are extremely traumatic and any additional factors only pile on. “That’s not something people just decide to do, that’s very much a necessity for a lot of people,” Bishop says, adding that on top of that high level of stress, children as young as infants are being separated from their caregivers.

“As a child, you’re forming your most important bonding with your caregivers – your trust, all those things that help you navigate your own relationships and needs. We are literally putting children in cages where they are being treated worse than zoo animals. That’s something a lot of children won’t be able to come back from.”

Melanie Arroyo Perez is a licensed professional counselor (LPC) in Kansas and provisionally LPC in Missouri who recently underwent the U.S. citizenship process, one she describes as an ultimately bittersweet experience. “It felt like a chore but also like a duty – it didn’t feel like a celebration.” Perez also specializes in trauma work including Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), domestic violence (DV), immigration-related stories, racial trauma and cultural identity development issues. She especially prioritizes advocacy and awareness for those affected by systemic forms of oppression, explaining that her goal is to help change clients’ perspectives to see the problem isn’t inherently in them, but the system.

“If we were to define trauma in a very simplistic way, it would be experiencing something that is out of your control, and is completely horrifying or terrifying in some way, and in no moment do you get a say or a choice – you are completely disempowered.”

Short-term effects of childhood separation and trauma

In the short term, mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and various levels of PTSD can develop. According to Bishop, the disruption of any normal sense of home or routine also causes a numbing phase that could lead to extremely oppositional behavior interfering with trust between children and their caretakers. “It’s going to rewire everything they know. A lot of times we see a big delay in development generally, physically, and mentally.” In her experience, the attachments are severely affected when parents and children are separated for prolonged periods of time.

“It’s going to lead to very intense, prolonged PTSD in children that will affect their ability to form attachments with caregivers or any other kind of intimate relationship due to the trauma of that separation and all the foreign people who are around them. It’s not like we’re placing them in a home – they [the children] are basically being thrown in a room and given bare necessities to survive, if that.”

Bishop also points out that oftentimes, children forcibly separated from their families are “brainwashed” that their caregivers are bad or criminals, causing an intense distrust when reunited. Children are frequently made to believe, from a combination of the trauma and potential manipulation from the detaining forces such as ICE, their parents left them and voluntarily put them in this situation.

Perez adds the separation is just as debilitating for the parents who now carry an “inappropriate guilt” that they failed and disappointed their children. “This may drive a wedge between them where they may not understand each other and be able to form those healthy bonds.”

Long-term effects

Citing Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) symptoms such as the fear of abandonment and poor attachment spirals, Perez fears how these children might carry trauma within them and how it will impact their ability to trust the world around them. “Are they going to feel safe? Are they going to feel protected in the very country they came to seeking that safety and protection?”

Along with the various traumatic impacts on mental health, Bishop stresses that developmental issues and learning disorders are linked to early separation in childhood because of the lack of foundational information gained through bonds with a caretaker. These children’s abilities to function and learn will be affected for the rest of their lives. “We’re not seeing any of those results yet, we are barely at the cusp of that,” Bishop says. “I don’t even want to think about 10 years from now when those kids get to high school age.”

Mental health in Latinx communities

While sufficient mental and physical care is critical for those affected by family separation, especially in the cases of those at the border, both women agree that barriers including accessibility, affordability, transportation, technology, cultural stigmas, and racial biases affect the ability to receive proper care. Clients in rural areas such as Kansas and Missouri especially face problems if they do not own vehicles, smart phones or internet, preventing them from both physically and virtually attending appointments or accessing documents such as the paperwork required to get their children back. These factors are only worsened by COVID-19 as many legal processes including this type of reunion require in-person signatures.

As an advocate for her clients facing racism or cultural prejudices, Perez warns of the social and systemic barriers specifically preventing the Latinx community from accessing mental health services. Social stigmas that therapy is only for wealthy white people, rowdy children, or those deemed “crazy” not only prevent Latinx people from seeking therapy, but also from discussing mental health within their communities. Perez often sees an almost shameful modesty from clients deciding their problems aren’t as bad as others’ and choosing not to “take someone else’s place” in therapy.

She sees several systemic barriers for Latinx people specifically accessing mental health services including a lack of multilingual counselors, flexible availability and daycare services. Because many Latinx clients are blue collar workers and/or have children with them during the day, they may only have time for therapy during evenings or weekends or may need someone to watch their children so they aren’t in the room during counseling. Perez especially stresses the complexity of processes while navigating the mental health system as a Latina woman. “Every day I’m running into something new I didn’t know about insurance, state limitations, budget cuts – we need to find ways to make it more accessible and easier to navigate.”

Above all, the overwhelming lack of Latinx representation in the mental health industry poses a glaring problem for communities seeking care. “We’re very thankful that people are finally realizing we all need mental health support, but what I’m noticing is we don’t necessarily have enough supply to meet that demand and especially within the Latinx community.” She explains that because of social stigmas, Latinx kids are not raised to want to go into mental health professions, especially because these children often are more interested in immediately getting to work to provide for their families rather than pursue an expensive master’s degree. Even if they do, they aren’t “seen or supported” she says, mentioning even she almost dropped out after realizing she was the only woman of color in her cohort at the time.

The need for culturally-aware care

Perez believes breaking down these mental health barriers begins with providers. “We need to start with some level of humility and accountability and taking a hard look at ourselves and our professions, acknowledging that we have inflicted harm on communities of color in the fields of therapy and social work. We are not absolved from that system of policing. We talk about children being separated at the border, but there are children who are also separated from their families here in our town because of those cultural misunderstandings from social workers and placing children in foster homes. Don’t get me wrong – many of those cases are well-merited. But there are and have been cases where those separations have been the result of not having cultural awareness.”

For patients of color at risk, she recommends asking questions and setting expectations before seeking care. The intake process for counseling can be traumatic when laying out life experiences and if the provider has certain requirements or specifications clients must meet, including health insurance, it may do more harm than help if they are continuously turned away. She also recommends familiarizing oneself with what ethics codes their provider’s specific profession must adhere to, notifying them that you are aware of these and will be holding them accountable and asking where they stand on certain political issues.

“We’re supposed to be sealed vaults, we do not do self-disclosure, but if I see a client who comes from a different background and they ask me where I stand on certain political issues, I’m going to tell them. My guess is they want to make sure they feel safe; I understand why they’re asking me that.” If a therapist refuses to give a clear answer or tries to prevent outside support such as family or friends being involved in their care plan, Perez recommends either speaking up or looking elsewhere. “You should advocate for yourself always. Don’t feel like the therapist has control over your sessions or your treatment. You have a say in how that treatment goes.”

Perez commends those who continue to seek care and healing for themselves and their loved ones, despite stigmas and biases within the mental health industry. “If there is any Latinx person reading this, I want them to know that while all of this conversation can be heavy, it doesn’t mean that we’re broken in any way. We can have traumas and depression and these difficult experiences throughout our lives, but we also need to give ourselves credit for the level of resiliency that we have.”