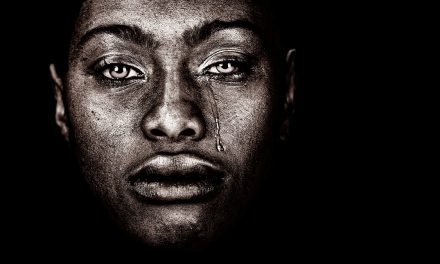

While largely overlooked by the general populace, medical racism has always existed. However, in a global pandemic, the inequality is blaring. Racial disparities among COVID-19 patients across the United States are intensifying the detrimental impact of the virus.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a disproportionate number of black people have been hospitalized due to COVID-19. Additionally, in New York City, where the virus is hitting hardest, black people die of COVID-19 at double the rates of their white counterparts. Hispanics face similar disadvantages in light of the pandemic.

Although COVID-19 is a new virus, the toll that it’s taking on minority communities has built up for decades, due to lack of access to care and medical mistreatment. People in communities of color face health care disparities, and they are more likely to live in heavily polluted areas with little to no access to whole and fresh foods. This results in poorer outcomes regarding health and wellness among minorities. Minority communities endure higher instances of asthma, high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes – all preexisting conditions that increase a person’s risk of complications or death when facing COVID-19. People of color are also more likely to work in service industries – such as food, transportation, sanitation, and retail – making them essential workers who are exposed to more people, leaving them further at risk of contracting the virus. Many of these jobs don’t have health benefits and offer no hazard pay in the midst of a pandemic.

Social determinants of health include but aren’t limited to housing, food, healthcare, employment, education, public safety, and transportation. Poverty, redlining, and underfunding of educational and healthcare institutions in minority communities obstruct the quality of life people across the country need to stay healthy. Even before coronavirus, black life expectancy was shorter than that of other races, according to the CDC. This is exacerbated in the face of a global pandemic.

The study of the link between morbidity and class goes back 300 years, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). In 1849, one doctor, Rudolph Virchow, said that the focus of medicine shouldn’t be to make individuals better but to heal society as a whole. In France, Louis-René Villermé suggested that school and working conditions should be improved to reduce mortality among the lower class. This realization also persisted in the United States when a 1983 report by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) stated that while the country as a whole experienced generally good health, black people and other minorities experienced “the burden of death and illness” greater than the rest of the American population.

Discrimination against African Americans in the health sphere goes back centuries and persists to this day. Its prevalence creates unconscious – but sometimes covert – bias among medical professionals, and can only be exacerbated during a public health crisis unless addressed.

According to the CDC, African Americans make up one-third of all confirmed COVID-19 cases in the United States while only making up 13 percent of the population. In Chicago, for example, 72 percent of COVID-19 deaths were among black residents even though African Americans only make up 29 percent of the city’s population. However, even with mounting evidence that COVID-19 is ravaging the black community, the numbers surrounding the crisis aren’t being fully reported.

In addition to black people, indigenous peoples of the U.S., particularly the Navajo Nation, are being hit hard by COVID-19. According to CNN, the Navajo Nation’s COVID-19 death toll is greater than that of 13 states combined. Many of those who live on the reservation are without running water or electricity, making sanitation and maintaining health more difficult. Like black people, indigenous people also suffer higher rates of high blood pressure, heart disease, asthma, diabetes, and other preexisting conditions that complicate COVID-19. According to the National Indian Health Board, only half of the tribal governments surveyed have reported receiving any COVID-19 information from federal or state governments. Additionally, their confirmed cases are being left out of demographic data, leaving the impact of their deaths largely unfelt by the rest of the country.

The Indian Health Service is underfunded, even though Native Americans traded land with the U.S. government in exchange for services. The Navajo Nation and other tribes have sued the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury in order to secure federal relief funds. In addition to lack of healthcare, underfunding of tribal governments and communities causes housing shortages. Without enough space, social distancing is nearly impossible. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), 16 percent of indigenous households are overcrowded.

Lack of access to COVID-19 testing and other healthcare is killing minority communities. Black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) aren’t inherently more susceptible to the virus. However, the systematic disadvantages they face makes their prognosis much bleaker than the rest of the population.

While this pandemic is a crisis that everyone in the nation is facing, some are closer to the frontlines than others. As long as disparities in healthcare exist under standard circumstances, more people will always die when we’re faced with what we’re dealing with now. The result of BIPOC being disproportionately affected by COVID-19 is the cumulative result of systemic prejudice and neglect of the unique needs of minority communities.

The way to combat this is to point out and uproot unconscious biases that medical professionals might carry. Studies show that even people of color who are fully insured and make a considerable amount of income have worse health outcomes than their white counterparts. This points to the fact the disparities not only lie in resources, but quality of care. The discrimination that minorities face from doctors and nurses make them more apprehensive to go to the hospital in the first place. The reluctance to seek treatment leads to sicker patients and more dire outcomes. On the other hand, doctors may feel misunderstood by their patients, while patients are afraid to ask questions or advocate for themselves for fear of being misunderstood or judged.

It takes a conscious effort and a willingness to be honest about the state of our healthcare system in order to tackle this issue. Doctors and nurses can’t be thanked enough for putting themselves directly in harm’s way to take care of us and our families – not only during a global pandemic, but every single day. However, it’s important that the people we trust with our lives and our loved ones are doing absolutely everything they can to listen to our concerns and care for us, regardless of race or ethnicity. Additionally, systems must be mobilized to combat food deserts and housing insecurity in minority communities.

If this pandemic has taught us anything, it’s that we are all intricately connected. How else could one infection halt the entire globe? Therefore, the health of America is every citizen’s responsibility. We carry this responsibility by caring for one another and speaking out for each other. This is how we defeat the virus.