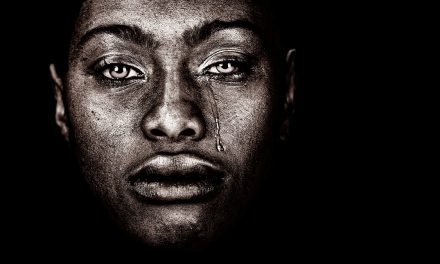

Breastfeeding has been linked to various benefits for infant and maternal health. However, a lack of access to culturally competent health care and breastfeeding support has led to many health disparities affecting Black birthing people and their children.

Black Breastfeeding Week 2022 celebrates a decade of creating a foundation of lactation support built on racial equity, cultural empowerment, and community engagement. From August 25-31, 2022, organizations raise awareness of the barriers to breastfeeding among Black women and birthing people and their impact on Black infant health.

According to the organizers of Black Breastfeeding Week, this event is necessary to identify and acknowledge five main points surrounding this conversation:

- Diet-related disease among Black people and infants.

- Desert-like conditions in Black communities.

- High rates of Black infant mortality.

- Unique cultural barriers among Black women and birthing people.

- The lack of diversity in the lactation field.

Recognizing and addressing these concerns and the barriers to breastfeeding among Black birthing people can help researchers, care providers, community-based organizations, and parents make impactful improvements to health and mortality disparities among Black birthing parents and infants.

Disease and Mortality in Black Infants

According to the Office of Minority Health, the Black infant mortality rate is 2.3 times that of white infants. The leading causes of Black infant mortality are being disproportionately born too small, too sick, or too soon. In 2018, Black infants were four times as likely to die from complications related to birth weight than white infants and twice as likely to die from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

Because nutrition (or lack of) is linked to health, disparities in one’s diet can often lead to higher risk for diet-related chronic diseases and conditions, morbidity, and mortality. Evidence from a decade-long study by the American Journal of Preventive Medicine shows diet-related health disparities vary by race and ethnicity, education, and income level.

These health disparities are predominantly related to social determinants of health, rather than biological differences. Many Black communities have food deserts, with a stark lack of grocery stores and fresh produce compared to fast food restaurants and convenience stores. As a result, many families spring for the low price, proximity, and round-the-clock availability of fast-food meals.

However, access to affordable nutritious foods is not enough. Providing healthy meals for one’s family also requires the means to do so, including a clean home equipped with working utilities and cooking appliances. If a family is homeless or living in a shelter, or struggling to keep up with bills, the ability to eat nutritiously becomes even more difficult.

Because of the desert-like conditions in Black communities, diet-related diseases such as diabetes, stroke, heart disease, and cancer are more prominent. Black communities specifically have higher rates of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and obesity compared to white communities.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), breastfeeding offers several benefits to both the infant and mother that can help reduce the risk of disease and death. In addition to providing essential vitamins and minerals, breastfeeding is also associated with reduced risk for infections, type 1 diabetes, obesity, and SIDS among infants. For mothers, breastfeeding can reduce high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and ovarian and breast cancer.

Because Black mothers and infants are at higher risk of disease and mortality, improving rates of breastfeeding within Black communities could significantly improve Black maternal and infant health. However, an overwhelming lack of support for Black breastfeeding currently maintains this disparity gap and will continue to do so without proper awareness, acknowledgement, and action.

Black Breastfeeding Barriers

Although there are many barriers to breastfeeding, Black women and birthing people are linked to a unique cultural history dating back to slavery that still carries consequences today. Black women’s role as wetnurses, for example, carries generations of trauma that weigh on today’s mothers. Black mothers were forced to prioritize caring for the children of their owners, to the detriment of their own children’s health. To this day, the loss of Black babies to this practice has left a transgenerational wound on Black birthing people that can and often does have an effect on whether or not they choose to breastfeed.

Because the history and development of modern medicine also possesses ties to slavery, obstetric racism is still present in all levels of health care, affecting quality of care and support. The result is misconceptions about Black birthing people continuing to trickle down, leading to a false belief among providers nationwide that Black families aren’t interested in breastfeeding and don’t require education or support.

As this myth has perpetuated, advocacy efforts for breastfeeding have become increasingly white female-led. White women serving as the face of breastfeeding has only exacerbated myths about the practice, reiterating to medical spaces as well as communities at large that only white women are interested in breastfeeding. As a result, breastfeeding has become stereotyped among many Black communities, making it especially difficult for new Black mothers to break the cycle and receive support, even from family and friends.

Lack of Diversity in Lactation

While the historical context of medical racism and breastfeeding misconceptions cannot and should not be untethered, change in representation in the lactation field is possible and offers a ray of hope. Increasing the diversity in both study populations and among research teams can help providers better understand the communities they serve and the specific needs of their patients.

According to the organizers of Black Breastfeeding Week, there currently exists a lack of representation in the lactation field for experiences across the income spectrum, geographical locations, communities across the African diaspora, and LGBTQ+ communities. There is a great need to diversify the research workforce and encourage researchers from these communities to ask questions, analyze data, develop and test interventions, and develop conclusions and recommendations that center the communities they are from.

Increasing representation throughout the research workforce, as well as acknowledging the historical context of Black breastfeeding and obstetric racism, creates the opportunity for more culturally competent lactation professionals. With more providers dedicated to offering breastfeeding education and support to Black mothers and birthing people, disparities in health and death can be significantly reduced.

However, effectively improving Black maternal and infant disease and mortality rates requires community change, too. Individual actions by mothers and their care providers cannot make up for the gaps left by unmet social determinants of health, such as lack of access to affordable health and dental care, stable housing, working utilities, nutritious food, mental health support, prenatal and postpartum support, and more.

Recommendations and Resources

To address the disparity gap in breastfeeding, the CDC encourages hospitals to implement evidence-based practices that support breastfeeding. Initiatives such as the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding have been found to improve overall breastfeeding outcomes and decrease racial and ethnic inequities.

Health departments are further encouraged to develop culturally relevant initiatives or refocus current promotion efforts for breastfeeding to better target their highest risk populations. Improving lack of diversity in the lactation field prior to making such changes is crucial to ensure that revised efforts are developed through a lens of racial equity and reproductive justice.

The CDC also recommends several maternity care practices that support breastfeeding and help reduce health disparities, including skin-to-skin contact, “rooming-in,” and pacifier use during hospitalization. These practices offer a variety of benefits to both the mother and infant, including helping to initiate breastfeeding, stabilizing glucose levels, reducing the risk of SIDS, and more.

Because many mothers return to work following birth, lack of breastfeeding support in the workplace can also create barriers, especially for Black women and birthing people who are already under-supported. However, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) requires employers to provide reasonable break time to pump as well as a private room (not a bathroom) to do so in.

This requirement lasts for one year following the child’s birth and includes that reasonable break time be allotted each time the employee needs to express milk. This requirement does not preempt state laws that may provide even greater protections such as compensating break time or providing break time beyond one year after the child’s birth.

Black Breastfeeding Support

In addition to breastfeeding resources from the CDC, there is a wealth of information for Black mothers and birthing people specifically from community-based organizations working to improve Black maternal and infant health disparities. Organizations who have previously or currently partner with Black Breastfeeding Week and are working to uplift breastfeeding in Black communities include:

- Black Mothers Breastfeeding Association.

- Black Girls’ Breastfeeding Club.

- CinnaMoms.

- Families for Equity.

- Dem Black Mamas.

- Baobab Birth Collective.

- Perinatal Health Equity Initiative.

The Irth app, created by Black Breastfeeding Week organizer Kimberly Seals Allers, helps Black and Brown women and birthing people have a more safe and empowered pregnancy. The Yelp-like app allows users to review their experiences with various providers and facilities, turning collective experiences into meaningful data that helps guide patient decisions when determining where to receive care.

Count the Kicks is a public health campaign and app proven to decrease stillbirth rates. By timing and counting the baby’s kicks during the third trimester, parents become familiar with their baby’s regular movements. This helps make signs of change or distress more noticeable, allowing parents more time to seek crucial emergency help and intervention. The Feel the Beat campaign specifically aims to reduce stillbirths among Black mothers and birthing people, who are at highest risk.

For individuals living in Missouri, a new program offers a continuum of care for mothers that actualizes compassion, dignity, and equity. The MaIH Project, which stands for Maternal and Infant Health, connects pregnant and birthing people with health care and social services to support them and their families from pregnancy through postpartum.

The program utilizes community-based organizations to ensure that all the parents’ needs are met, including gaps left by unmet social determinants of health. To learn more and receive help, call or text 844.860.0111 or visit https://altruism-media.org/the-maih-project/.

Black Breastfeeding Week 2022 will feature several virtual events that celebrate and uplift stories about breastfeeding while Black as well as provide insight into current research and recommendations for future improvements. Learn more and get involved.