Opinion Editorial

I like to believe most people wish to make the world a better place. I like to believe most people would say that everyone has value. I like to believe most people want the best for humanity and the planet we call home, even if we disagree about exactly what that means.

And I like to believe those shared goals make it possible, even in today’s violently polarized world, to have real conversation about our beliefs. Even as it becomes increasingly obvious how politics directly impact the health and safety of ourselves and our neighbors, our families and our friends, as more and more personal pain becomes attached to hotly-debated topics, I believe in the power of political discourse from a place of mutual desire to make the world a better place. Maybe that faith makes me an optimist, but believing common ground is impossible makes common ground impossible. Now, more than ever, we must at least try.

Let me propose this, then, as our starting point: All people have value.

We all matter just because we’re human. That statement sounds straightforward, but what does it actually mean to say that everyone has value? The answer to that question, I believe, holds the key to the common ground that today so desperately needs.

The trolley problem is the most famous way to examine the question. It goes like this: a trolley is headed for five people who are stuck in its path. The trolley can be diverted to a side track, where only one person is stuck in its path. You can choose to either divert the trolley to the side track, which will kill one person, or allow the trolley to continue down the main track, which will kill five people. What do you do?

The trolley problem is what’s called a “thought experiment,” in which you are faced with an imaginary problem in order to measure what you instinctively feel is the right thing to do. When polled, the vast majority of people (around 90%) consistently choose to divert the trolley so that one person dies and five others live.

Doing the most good for the most people seems obvious, but killing one to save five is not always the popular answer. In another thought experiment, a hospital admits six new patients: five in desperate need of organ transplants, and one perfectly healthy person. Should the surgeons kill the healthy patient and harvest those organs to save the lives of the five others? Here, very few people believe the right thing to do is kill the one to save the five — but if the math is the same, what’s the difference?

Though it may seem complicated, the answer is simple: We tend to disagree with treating people as a means to an end, instead of as ends unto themselves.

In the trolley problem, we find sacrificing one to save five morally acceptable because diverting the trolley is what would save the lives of the five others. The death of the one person is a consequence of diverting it, not the means by which the five could be saved. If, instead, you had pushed someone in the way of the trolley to stop it before it killed the five people, then the pushed person’s death would be the means by which you saved the five. Similarly, in the hospital problem, killing the healthy person is the means by which the surgeons would save five others’ lives. They are used to save the rest at the expense of their own life.

By treating someone as a means to an end, we make them into a tool to accomplish our goals without allowing them a say in what happens to them. When surveyed about thought experiments, most people are, predictably, much less favorable of choices which use a person as a means to an end. At last, we seem to have an answer for our earlier question: What does it mean to say all people have value? No one should be treated as a means to an end. We are all ends unto ourselves; we are all worthwhile goals.

Naturally, with our answer comes a hundred new questions. What does that mean for politics? For medicine? Surely, if health care is all about taking care of people, then it must never treat people as a means to an end.

Right?

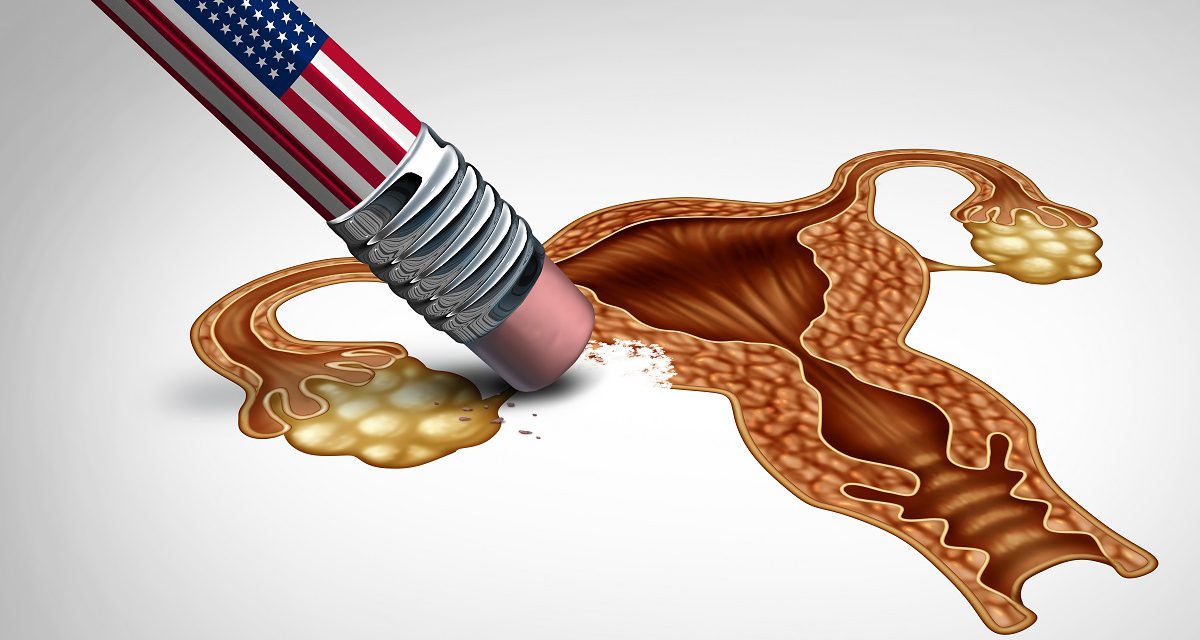

Well, as a quick review of the infamous Tuskegee Experiments will tell you (among a thousand other cases of doctors and scientists using the bodies of people of color in appalling ways), that’s unfortunately not the case. From policy to practice, medicine still fails to avoid treating people as a means. Now, reproductive health care is at the epicenter of this failure. Facing red tape around many kinds of contraceptives, ignored in favor of the husband’s wishes, and increasingly unable to easily access abortion care, anyone with a uterus is at constant risk of being reduced from a person to a means of birthing.

Let’s start with access to contraceptives. Though many religious beliefs play into this topic, our nation is, by its own Constitution and the wishes of the founding fathers, secular. It must neither enforce nor deny any one religious agenda. Banning contraceptives (or leaving all decisions about contraception to a woman’s husband, as if her body were his property, which immediately makes her a means to his end) would plainly be enforcing a religious agenda, just as forcing everyone with a uterus to use contraceptives would be denying religious (and personal) freedom. The middle ground, then, must be making contraception freely available and offering the education needed for the public to make informed decisions on their own behalf, with their own agency, for their own ends. Policy, however, does not guarantee this middle ground, and people suffer as a consequence.

Religious freedom and freedom from religion aside, law and policy are meant to protect and support the health of the people. Still, despite countless studies about how ineffective and harmful they are, abstinence-only programs are still permitted in schools and funded by the federal government, to the detriment of their students. We have known for decades how ineffective these programs are. How can we treat a harmful agenda as a more worthwhile pursuit than the well-being of the students who have no say in their education? Who could soundly claim to have the moral high ground, upon seeing any curriculum cause direct, negative health outcomes for children, for continuing to force that curriculum on students? Surely, if we treated their education as a means toward the ends of their health, we would not allow this.

Though education and access to contraception are, from a moral standpoint, fairly straightforward, abortion does not seem so clear-cut. After all, if people should be an ends and not a means, and everyone disagrees about what counts as “people,” then sorting out what is and isn’t an ends must be a messy process.

Personally, I’ve always been alarmed by the idea that an embryo is the same as a full human from the moment it has some arbitrary characteristic, whether it be a heartbeat or just fertilization. None of the proposed landmarks stand out to me as more inherently right or true than the others, which implies that the landmarks themselves might not be the point. In all honesty, I don’t think the people arguing for them truly believe an embryo is a person. Faced with the choice to save either five viable embryos or one screaming newborn from a burning building, I believe they would save the newborn. But nor are these people necessarily dishonest or malicious. I believe they are genuinely invested in protecting the potential person that embryo could become — without distinguishing between potential and actual. Understandable though that perspective is, taken to its logical extreme, if we punished anything that prevented a potential person from being born, every unfertilized egg or sperm would also be a criminal offense. I don’t think many of us would be on board with that policy.

It’s all fine and well to claim that others are wrong, but as any philosopher knows, the hard part is figuring out what’s right. Let’s look at the problem at hand again. Even if abortion sparks disagreement about what counts as an ends, it is much easier to determine what is being used as a means. Even if we say, for the sake of argument, that a newly-fertilized embryo is a person, there’s no arguing that embryos are dependent upon the body of their parent to survive. If, therefore, we deny the parent a say in whether to continue allowing the embryo the use of their body, if we demand they permit the embryo to use them until the moment it doesn’t depend on them, we have made the parent a means to an end. Even more so, given the risk every pregnancy carries to the parent’s life, and the dangers of making it harder to get an abortion. If we commit to the belief that the birthing parent is not a means to an end, that they are an ends, that they have value, then we must allow them to have a say.

How painful, to see a potential person be prized and valued over the actual person right in front of us.

This is, to be sure, a very long-winded way to say “I’m pro-choice,” but I wholeheartedly believe the reasons for any moral stance are just as important as the stance itself. If we don’t hold our morals to consistency, we might as well be arbitrarily deciding right and wrong based upon our own biases. Take, for example, those who support Texas’ self-defense laws and yet oppose abortion even in cases where the mother’s life is at risk. If I am within my rights to shoot a trespasser I believe is dangerous, then even if a fetus is a person, surely I am within my rights to defend myself against a person doctors have told me is threatening my life from within me. These views only coexist if we don’t think about why we have them and hold ourselves to moral consistency.

If we want to find common ground and work together to create change, to make the world a better place, we have to start with understanding why we believe what we believe. Everyone matters. Everyone deserves a better world, and that world starts with us working together to make it better.